When your child gets an ear infection or you develop a urinary tract infection, you expect a simple course of antibiotics to fix it. But in 2025, that’s no longer guaranteed. Across the UK, the US, and parts of Africa and Asia, antibiotic shortages are forcing doctors to delay treatment, use riskier drugs, or send patients home with no medicine at all. This isn’t a temporary glitch-it’s a systemic crisis fueled by broken economics, manufacturing failures, and rising drug resistance.

Why Antibiotics Are Vanishing

Antibiotics aren’t like other medicines. They’re cheap, used for short courses, and often made as generics. That makes them unprofitable for manufacturers. While cancer drugs or diabetes medications bring in billions, a single course of amoxicillin might cost less than £2. With profit margins so thin, companies have shut down production lines. The European Court of Auditors reported that manufacturing facilities for sterile injectables-like penicillin G benzathine-require expensive, strict controls. But with prices down 27% since 2015, few manufacturers see the point in investing. Brexit made things worse in the UK. Drug shortages jumped from 648 in 2020 to 1,634 in 2023, with antibiotics among the hardest hit. The US isn’t far behind. As of December 2024, the FDA listed 147 active antibiotic shortages. Globally, 37 antimicrobials are officially in short supply, second only to IV fluids in frequency of shortage.What’s Running Out-and Who’s Affected

Some of the most commonly used antibiotics are vanishing:- Amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate: After a January 2023 shortage, use dropped by 55% and 69% respectively across 22 European databases.

- Penicillin G benzathine: In short supply since 2015, it’s critical for treating syphilis and preventing rheumatic fever in children.

- Cephalosporins: First-line for many infections, but increasingly ineffective due to resistance.

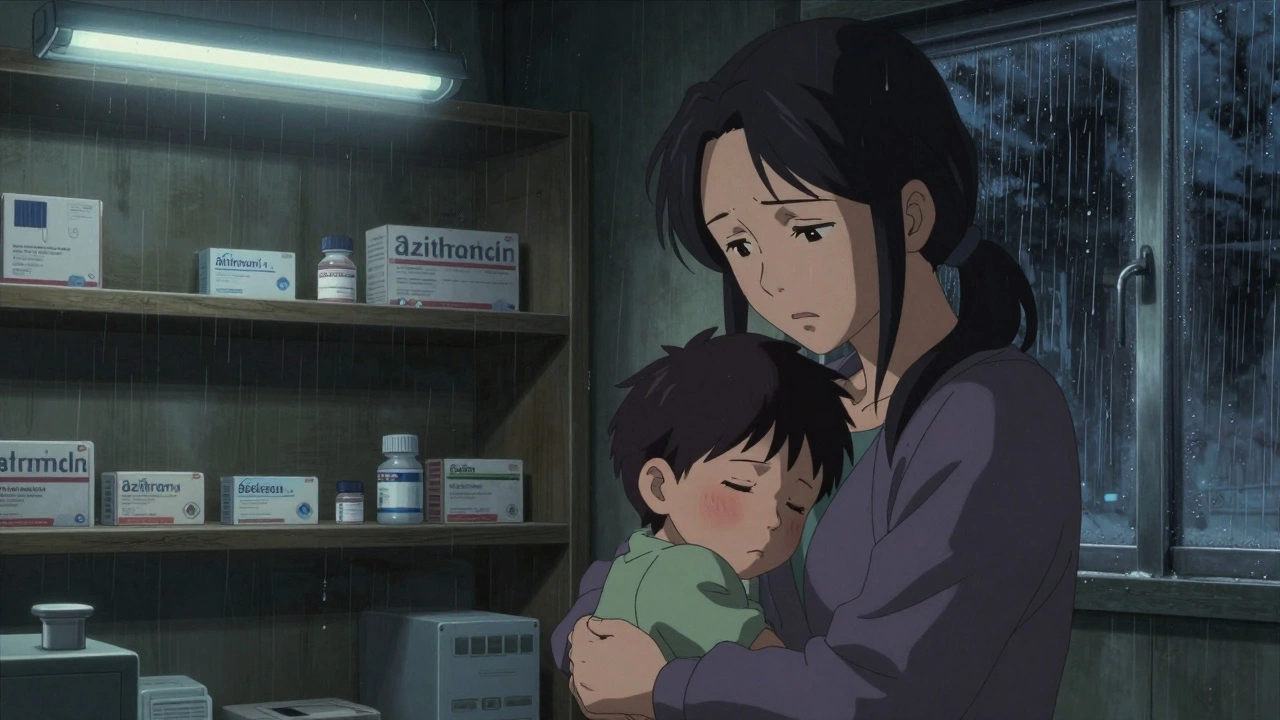

- Azithromycin: Used for pneumonia, ear infections, and STIs. A mother in Mumbai reported her child’s pneumonia was delayed 72 hours because it wasn’t available.

The Deadly Domino Effect

When your first-choice antibiotic isn’t available, doctors turn to alternatives. But those alternatives aren’t safer-they’re often stronger, more toxic, and accelerate resistance. For example: if a common E. coli infection doesn’t respond to amoxicillin or ciprofloxacin, the next step might be a carbapenem like meropenem. But carbapenems are reserved for last-resort cases. Overusing them creates superbugs like Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to nearly all antibiotics. The WHO reports that over 40% of E. coli and over 55% of K. pneumoniae are now resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. When those fail, clinicians are left with colistin-a toxic, last-ditch drug once abandoned due to kidney damage. One California infectious disease specialist told the APHA forum she had to use colistin for a routine UTI because nothing else was available. A Reddit user in Bristol wrote: “We’re forced to pick between treating the infection and making resistance worse. There’s no good option.”

What Happens When Treatment Is Delayed

Delaying antibiotics doesn’t just mean longer sickness-it means complications, hospitalizations, and death. A child with pneumonia who waits three days for azithromycin can develop sepsis. A pregnant woman with syphilis without penicillin G benzathine can pass the infection to her baby, causing stillbirth or lifelong disability. In hospitals, delayed treatment leads to longer stays, higher costs, and more deaths. A 2025 survey found that 62% of hospitals reported increased patient complications directly linked to antibiotic shortages. In one UK hospital, a patient with a kidney infection developed septic shock after waiting five days for a replacement antibiotic. The patient survived, but spent three weeks in intensive care.Why Alternatives Don’t Work

Unlike painkillers or blood pressure meds, antibiotics don’t have many interchangeable options. If you run out of ibuprofen, you can use paracetamol. If you run out of metformin, you can switch to sitagliptin. But for many bacterial infections, there’s no backup. The problem is specificity. Antibiotics target certain bacteria. If a drug doesn’t cover the right bug-or if the bug is already resistant-it won’t work. And resistance is rising fast. Between 2018 and 2023, resistance increased in over 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations tracked by WHO. In some regions, one in three urinary tract infections can’t be treated with first-line drugs.

What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

Some solutions are in motion, but they’re slow and underfunded. The WHO announced a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative in October 2025, aiming to stabilize supply by 2027. The US FDA approved two new manufacturing plants in early 2025, expected to cover 15% of current shortages by late 2025. The European Commission is pushing its Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe, which includes incentives for antibiotic production. Hospitals are trying to adapt. Johns Hopkins Hospital reduced unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 37% during shortages by using rapid diagnostic tests to identify infections faster. California launched a regional sharing network that cut critical shortage impacts by 43% across 12 hospitals. But progress is uneven. Only 37% of US hospitals meet all WHO standards for antimicrobial stewardship. Pharmacy teams are overwhelmed-average workload increased by 22% per pharmacist. Rationing decisions are stressful and inconsistent. One hospital might give a child amoxicillin; another might give nothing.What You Can Do

As a patient, you can’t fix the supply chain. But you can help reduce the pressure:- Don’t demand antibiotics for colds, flu, or sore throats-these are viral. Antibiotics don’t work on them.

- Take your full course if prescribed. Stopping early leaves resistant bacteria alive.

- Ask if there’s an alternative if your pharmacy says it’s out of stock. Sometimes a different formulation or brand is available.

- Support policies that fund antibiotic production and improve global access. This isn’t just a healthcare issue-it’s a security issue.

The Future Is Bleak-Unless We Act

Without major intervention, the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance predicts antibiotic shortages will rise 40% by 2030. That could mean 1.2 million extra deaths each year from infections we once cured easily. The WHO’s goal-to have 70% of antibiotic use come from the safer ‘Access’ group by 2030-is already behind. In 2024, only 58% of global use was from this group. Meanwhile, the global antibiotic market grew just 1.2% from 2019 to 2024, while the rest of the pharmaceutical industry grew 5.7%. We’re treating antibiotics like disposable commodities. But they’re not. They’re one of the most important medical advances in human history. And if we keep ignoring the cracks in the system, we’ll wake up one day to a world where a scraped knee can kill you.Why are antibiotics running out if they’re so common?

Antibiotics are cheap, low-margin drugs made mostly as generics. Manufacturers make more money producing expensive cancer drugs or chronic condition medications. With profit margins too thin to cover strict manufacturing costs, many companies have stopped making antibiotics altogether. The result: fewer factories, less supply, and more shortages.

Can I buy antibiotics online if my pharmacy is out?

No. Buying antibiotics online without a prescription is dangerous and illegal in most countries. Many online sellers offer fake, expired, or contaminated drugs. Even if the antibiotic is real, using it without proper diagnosis can worsen resistance. Always consult a doctor before taking antibiotics.

Are there any new antibiotics being developed?

Yes, but very few. Pharmaceutical companies are investing more in antibiotic R&D now, with funding expected to rise 22% by 2027. But developing a new antibiotic takes 10-15 years and costs over $1 billion. Even when new drugs are approved, they’re often reserved for last-resort use to slow resistance. Manufacturing capacity still lags behind need.

How do antibiotic shortages affect children?

Children are especially vulnerable. Many common childhood infections-ear infections, pneumonia, strep throat-rely on antibiotics like amoxicillin or azithromycin. When these are unavailable, doctors have to use broader-spectrum drugs that increase resistance risk. In low-income areas, children may get no treatment at all. A 2025 report from Mumbai documented a child’s pneumonia worsening into sepsis after a 72-hour delay due to azithromycin shortages.

Is antibiotic resistance getting worse because of shortages?

Yes. When first-line antibiotics aren’t available, doctors use stronger ones like carbapenems or colistin. These are meant to be last-resort drugs. Overusing them speeds up the development of superbugs. WHO data shows resistance rose in over 40% of monitored pathogen-antibiotic combinations between 2018 and 2023. Shortages don’t cause resistance alone-but they push doctors to use drugs that make resistance worse.

Comments

Jennifer Blandford

Just got back from the pharmacy and they were out of amoxicillin for my kid’s ear infection. Told me to come back in 3 days. Three. DAYS. I’m not asking for a miracle-I’m asking for a basic medicine that’s been around since the 1950s. How did we get here? 😔

On December 10, 2025 AT 07:03

Haley P Law

THIS. I had to use colistin for a UTI last month because everything else was gone. My kidneys felt like they were being sandblasted. And the doctor just shrugged and said, ‘It’s the best we’ve got.’ We’re playing Russian roulette with antibiotics and nobody’s even talking about it. 🤬

On December 10, 2025 AT 14:47

Taya Rtichsheva

so like... if antibiotics are so cheap why dont we just make more?? like its not rocket science right?? also why are we still using penicillin in 2025 like its a vintage car??

On December 11, 2025 AT 12:14

Steve Sullivan

Look, I get it-profit drives everything. But we treat antibiotics like toilet paper. You don’t wait until the roll is gone to buy more. You stockpile. You invest. You fund the factories. We’ve been sleepwalking through this crisis while Big Pharma chases billion-dollar drugs for people who already have insurance. Meanwhile, a kid in Nairobi dies from a strep throat because the last vial of penicillin went to a hospital in Chicago that had a backlog. We’re not just failing healthcare-we’re failing humanity.

On December 11, 2025 AT 20:22

Simran Chettiar

The structural decay of antibiotic production is not merely an economic phenomenon but a symptom of a broader epistemological collapse in our global health governance framework. The commodification of life-saving pharmaceuticals under neoliberal paradigms has rendered essential medicines subject to market volatility, thus creating what can only be described as a bioeconomic paradox: the more universally necessary a drug is, the less financially incentivized its production becomes. This inversion of value logic-where utility is subordinated to profitability-represents not just a policy failure but a moral failure of unprecedented scale. The WHO’s 70% Access target is statistically insignificant when 92% of global antibiotic consumption occurs in low- and middle-income nations that lack the regulatory infrastructure to even monitor stock levels, let alone secure supply chains. We are not experiencing a shortage-we are experiencing the systematic erasure of medical equity.

On December 13, 2025 AT 16:01

Asset Finance Komrade

Interesting how we blame capitalism for this but never mention that the WHO’s own guidelines encourage overprescription in LMICs, which accelerates resistance and makes shortages worse. Maybe the problem isn’t profit-it’s poor stewardship. We need fewer antibiotics, not more. And we need to stop pretending that every sniffle needs a pill.

On December 14, 2025 AT 04:57

Andrea DeWinter

For anyone panicking about not finding amoxicillin-check local compounding pharmacies. They can make it from scratch if they have the raw powder. Also, some clinics have emergency stockpiles for kids and pregnant women. Don’t just give up. Call your county health dept-they might know where to get it. And if you’re a provider-use rapid tests before jumping to broad-spectrum. We’re not helpless. We just need to stop acting like it.

On December 15, 2025 AT 03:14

Anna Roh

So we’re all just supposed to sit here and wait for someone else to fix it?

On December 15, 2025 AT 13:13