Imagine trying to hear your spouse whisper across the room, but all you catch is muffled silence. Or sitting in a quiet classroom, struggling to understand a teacher’s voice even though they’re speaking clearly. This isn’t just bad luck - it could be otosclerosis, a condition where abnormal bone growth in the middle ear slowly steals your ability to hear low-pitched sounds.

Otosclerosis isn’t cancer. It’s not an infection. It’s a slow, silent process: bone that should stay firm starts growing in the wrong places, especially around the stapes - the smallest bone in your body, about the size of a grain of rice. When this happens, the stapes gets stuck. It can’t vibrate. And without vibration, sound can’t travel from your eardrum to the inner ear. The result? Progressive hearing loss that creeps up over years, often unnoticed until it’s too late.

How Otosclerosis Breaks the Sound Path

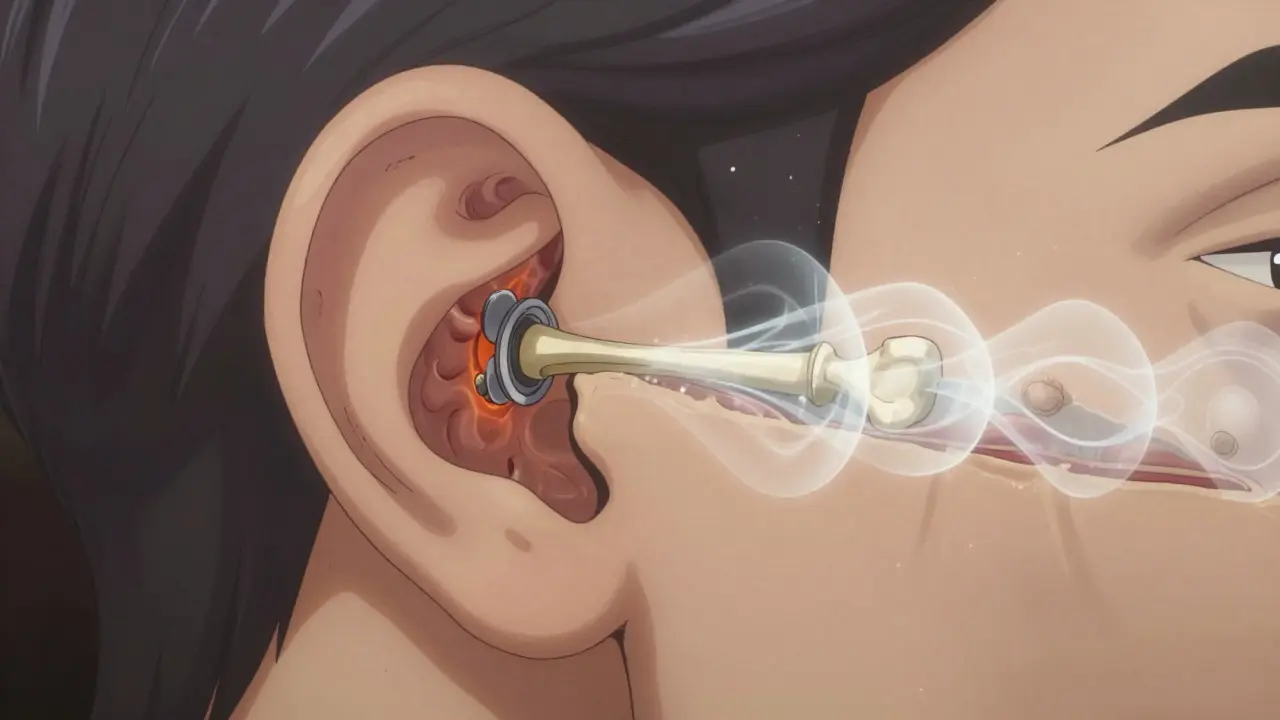

Your ear works like a chain. Sound hits the eardrum, which pushes on three tiny bones - the malleus, incus, and stapes. The stapes connects to the oval window, a membrane leading into the fluid-filled inner ear. When the stapes moves, it ripples that fluid, turning sound into nerve signals your brain understands.

In otosclerosis, the bone around the stapes footplate starts growing irregularly. Instead of dense, healthy bone, you get spongy, vascular tissue that eventually hardens into a fixed plug. Think of it like rust building up on a hinge until it won’t move anymore. This is called a conductive hearing loss - the sound isn’t lost, it’s blocked. Audiograms show an air-bone gap of 20-40 dB, meaning you hear better through bone conduction (like humming) than through air.

That’s why people with otosclerosis often say they hear better in noisy rooms. Background noise masks the low-frequency sounds they’re missing. But in quiet places - a library, a phone call, a whisper - everything disappears.

Who Gets Otosclerosis and Why

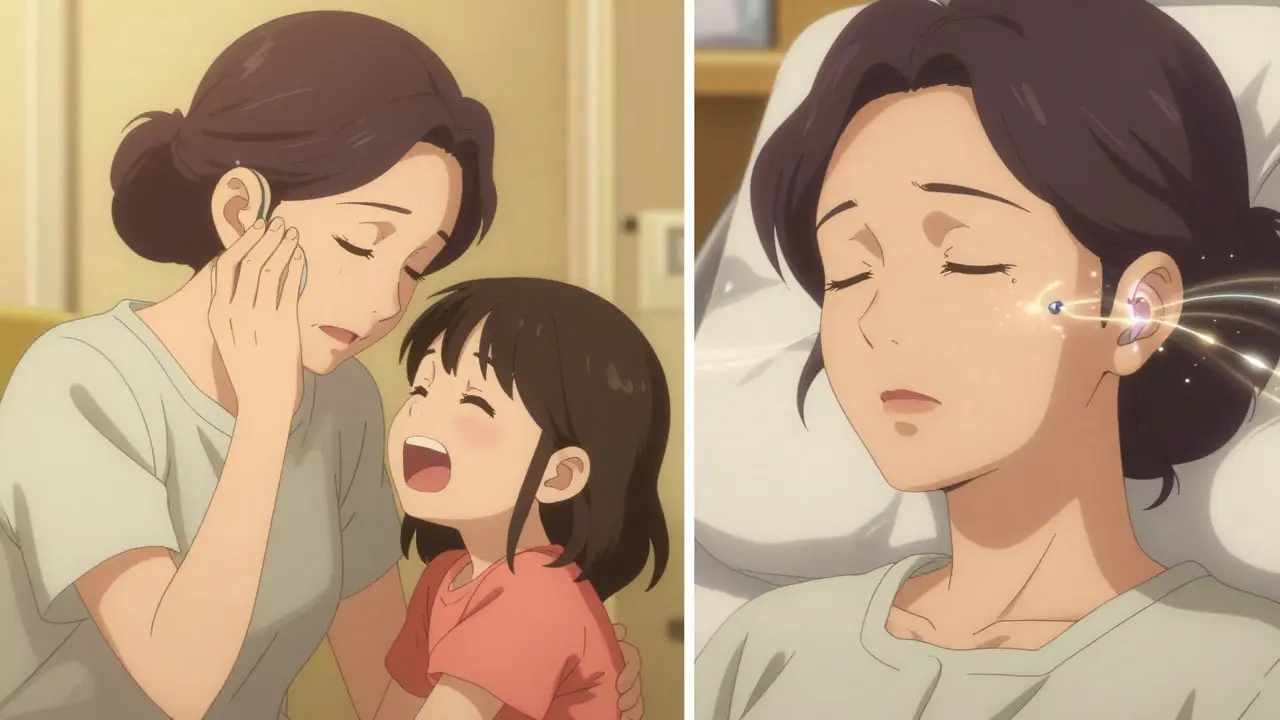

This isn’t random. Otosclerosis hits about 1 in 200 people in the UK and roughly 3 million Americans. It’s most common in women, especially between ages 30 and 50. If your mom or grandma had it, your risk doubles. Research from 2021 found 15 genetic links, with the RELN gene on chromosome 7 being the strongest. It’s not just inherited - hormones matter too. Pregnancy can make symptoms flare up, which is why many women notice hearing changes after having a baby.

Ethnicity plays a role. People of European descent have the highest rates (0.3-0.4%), while African populations have the lowest (0.1%). Scientists still don’t know why, but it’s likely tied to gene variations that affect bone metabolism.

It’s also not just about bone growth. About 10-15% of people develop cochlear otosclerosis - where the abnormal bone spreads into the inner ear. That shifts the hearing loss from conductive to mixed or even sensorineural. That’s harder to fix. And about 80% of patients report tinnitus - a constant ringing or buzzing - often so loud it disrupts sleep.

How It’s Different From Other Hearing Losses

Not all hearing loss is the same. Age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) hits high pitches first - think birds chirping or children’s voices. Noise-induced loss? Also high frequencies. Otosclerosis? It starts with low tones. You’ll miss the bass in music, struggle to hear men’s voices, or think your partner is mumbling when they’re not.

Compare it to Meniere’s disease: that one comes with spinning dizziness, ear pressure, and fluctuating hearing. Otosclerosis? Steady, slow decline. No vertigo. No pressure. Just a quiet fading of sound.

And unlike congenital hearing problems, where the bones never formed right, otosclerosis affects people who once heard perfectly. That’s why it’s so shocking when it hits. You didn’t expect this. You thought hearing loss was something that happened to older people.

Diagnosis: What Doctors Look For

Most people don’t realize they have otosclerosis until they get an audiogram. The test shows a clear air-bone gap - your bone-conduction thresholds are normal, but air-conduction is worse. Speech discrimination is usually still strong (above 70%), which helps rule out inner ear damage.

CT scans can show the telltale signs: radiolucent foci - small, dark spots - around the oval window, measuring 0.5-2.0 mm. These are early areas of bone remodeling. In advanced cases, the stapes footplate looks fused.

But here’s the catch: 22% of patients wait 18 months for a correct diagnosis. Why? Because primary care doctors often mistake it for Eustachian tube dysfunction - a common ear pressure issue. They’ll prescribe decongestants or nasal sprays. It doesn’t help. The bone is still growing.

Treatment Options: Surgery vs. Hearing Aids

You have two real choices: surgery or amplification.

Surgery - specifically stapedotomy - is the gold standard. Instead of removing the whole stapes (old method), surgeons make a tiny hole in the footplate and insert a prosthetic. A 2024 FDA-approved device, the StapesSound™ prosthesis, uses a titanium-nitride coating that cuts post-surgery adhesions. Clinical trials show 94% success at one year. The procedure takes under an hour. Most people go home the same day. Recovery is quick: avoid flying, heavy lifting, and water in the ear for a few weeks.

Success rates? 90-95% of patients regain functional hearing - meaning they can hear well enough without a hearing aid. One 45-year-old teacher told Tampa General Hospital, “I can finally hear my students whispering in the back row.”

But there’s a risk. About 1% of surgeries cause sudden, permanent sensorineural hearing loss. That’s rare, but devastating. That’s why informed consent is non-negotiable.

Hearing aids are the other path. About 65% of people start here. Modern digital aids can amplify low frequencies effectively. They don’t fix the bone - they compensate for it. They’re non-invasive, reversible, and covered by insurance more often than surgery.

But they’re not perfect. You’ll still struggle in noisy rooms. Background noise competes with speech. And if your hearing keeps worsening, you’ll eventually need surgery anyway.

What About Medications or Home Remedies?

No pill cures otosclerosis. But sodium fluoride - yes, the same stuff in toothpaste - has shown promise. A 2024 double-blind study with 120 patients found a 37% reduction in hearing deterioration over two years. It doesn’t reverse damage, but it can slow progression. It’s not FDA-approved for this use, but some otolaryngologists prescribe it off-label for patients with early cochlear involvement.

There’s no evidence that vitamins, supplements, or ear candles help. Don’t waste your money.

What Happens If You Do Nothing?

Without treatment, hearing loss worsens by 15-20 dB over five years. That’s the difference between understanding speech clearly and needing to lip-read. By the time you’re in your 50s, you might be isolated - avoiding calls, skipping family dinners, missing jokes.

And if cochlear otosclerosis develops, you lose the chance for full recovery. Once the inner ear is damaged, even surgery won’t restore normal hearing. That’s why early diagnosis matters.

The Future of Otosclerosis Care

Doctors are racing ahead. Genetic screening is coming. Within five years, polygenic risk scores could identify high-risk people before symptoms start. Imagine a simple blood test at age 25 that tells you your odds - then you get monitored yearly with audiograms.

But there’s a problem. Fewer surgeons are doing stapedotomies. Since 2018, the number of procedures has dropped 15% as younger otolaryngologists focus on cochlear implants. That means if you need surgery, you might have to travel farther to find someone qualified.

Still, otosclerosis isn’t going away. The American Academy of Audiology predicts it will remain the third most common cause of adult hearing loss through 2040. And with better tools and awareness, more people will get help.

Real Stories: What Patients Say

On Reddit’s r/HearingLoss, a user named MamaBear87 wrote: “I kept thinking my husband was mumbling until my audiogram showed 45 dB loss at 500 Hz.” That’s the low-frequency signature of otosclerosis.

Another, HearingHope42, said: “After diagnosis at 38, my hearing dropped from 25 dB to 55 dB in three years. Phone calls became impossible.” She now uses a hearing aid and is scheduled for surgery.

And then there’s the 92% satisfaction rate from Tampa General Hospital’s 2023 survey. People who had surgery didn’t just hear better - they reconnected with life. They heard their grandchildren laugh. They went back to church. They stopped asking people to repeat themselves.

That’s the real goal. Not just to hear sound. To hear life.